Internet and news services continued to be disrupted across Myanmar on Thursday, as the country’s military sought to secure their grip on power after deposing the democratically-elected government earlier this week.

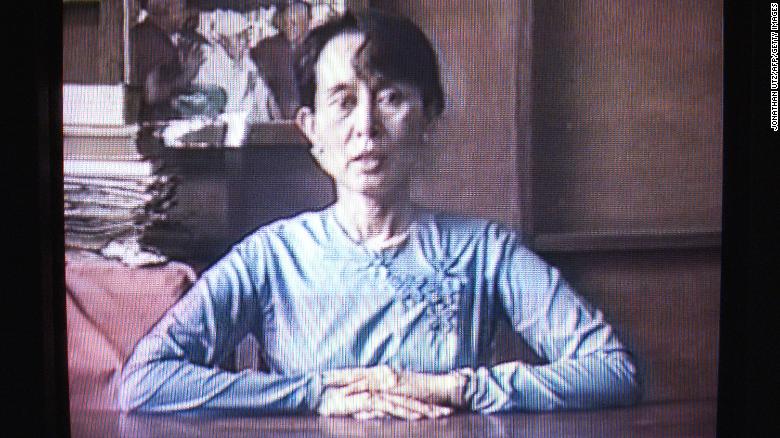

Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s de facto leader, along with President Win Myint and dozens of other senior figures in their National League for Democracy (NLD) were detained in pre-dawn raids Monday. Hours later, the military declared that power had been handed to commander in chief Min Aung Hlaing, in response to unfounded allegations of election fraud. A state of emergency was declared for one year.

Late Wednesday, an arrest warrant was issued for Suu Kyi over unspecified “import and export” offenses, while Win Myint was remanded in custody under the country’s Disaster Management Law, according to an NLD spokesman.

While the dramatic overthrow of Suu Kyi’s government attracted international attention, continued disruptions to internet access and communications mean that many in Myanmar may still be unclear about what is taking place.

Facebook, by far the largest online platform in the country, confirmed to CNN that its services were “currently disrupted for some people” as of Thursday morning, as independent monitors recorded widespread filtering of Facebook, WhatsApp and other platforms, even as basic internet access was returning in some areas.

Limited access to news and internet could affect the ability of people to get information or organize any response via social media. At one point on Monday, the only operational TV channel was the Myanmar military-owned television network Myawaddy TV. By Wednesday, some channels, such as DVB TV, were still off the air.

Speaking Wednesday, US State Department spokesman Ned Price said Washington was “disturbed” by reports of an arrest warrant being issued for Suu Kyi.

“We call on the military to immediately release … all detained civilian and political leaders, journalists, and detained human rights activists and to restore the democratically elected government to power,” Price said, adding that President Joe Biden viewed the military’s actions as a “direct assault on the country’s transition to democracy and the rule of law.”

Military in control

For more than 50 years, Myanmar — also known as Burma — was run by successive isolationist military regimes that plunged the country into poverty and brutally stifled any dissent. Thousands of critics, activists, journalists, academics and artists were routinely jailed and tortured during that time.

Suu Kyi shot to international prominence during her decades-long struggle against military rule. When her party, the NLD, won a landslide in elections in 2015 and formed the first civilian government, many pro-democracy supporters hoped it would mark a break from the military rule of the past and offer hope that Myanmar would continue to reform.

The NLD was widely reported to have won another decisive victory in a November 2020 general election, giving it another five years in power and dashing hopes for some military figures that an opposition party they had backed might take power democratically.

The sudden seizure of power came as the new parliament was due to open and after months of increasing friction between the civilian government and the powerful military, known as the Tatmadaw, over alleged election irregularities. The country’s election commission has repeatedly denied mass voter fraud took place.

Hundreds of NLD lawmakers were detained in the capital Naypyitaw Monday, where they had traveled to take up their seats. The junta has since removed 24 ministers and deputies from government and named 11 of its own allies as replacements who will assume their roles in a new administration.

Analysts have suggested the coup was more likely to do with the military attempting to reassert its power and the personal ambition of army chief Min Aung Hlaing, who was set to step down this year, rather than serious claims of voter fraud.

“Facing mandatory retirement in a few months, with no route to a civilian leadership role, and amid global calls for him to face criminal charges in The Hague, he was cornered,” Jared Genser, an international human rights lawyer who previously served as pro bono counsel to Suu Kyi, wrote for CNN this week.

Protests and strikes

So far, resistance to the coup has been relatively limited, both in part due to communications difficulties, and long memories of previous brutal crackdowns by the military, while ruled the country with an iron-grip for so long.

Doctors have pledged to go on strike, despite the coronavirus pandemic which is still dogging Myanmar, and there have been scattered calls for protests and work stoppages issued online, some in the name of the NLD.

Assistant Doctors at Yangon General Hospital released a statement pledging their participation in the “civil disobedience movement,” saying they will not work under a military led government and called for Suu Kyi’s release.

Video showed medical workers in Yangon outside the hospital Wednesday dressed in their scrubs and protective gear, while wearing red ribbons.

Myanmar’s Ministry of Information warned the media and public Tuesday not to spread rumors on social media or incite unrest, urging people to cooperate with the government following Monday’s coup.

“Some media and public are spreading rumors on social media conducting gatherings to incite rowdiness and issuing statements which can cause unrest,” the statement read. “We would like to urge the public not to carry out these acts and would like to notify the public to cooperate with the government in accordance with the existing laws.”

Fear of the military could be a powerful preventative against concerted action.

“When the military was last in charge, political prisoners like me were rounded up, sent to prison for decades, (put in) solitary confinement and tortured. We are concerned that if this state of emergency is not reversed, similar things will happen again,” said Bo Kyi, co-founder of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, and a former detainee himself.

“There is a fear that the military could continue persecuting officials, activists and crack down on ordinary people. But we have hope that Burma can return on its democratic path.”

Source : CNN News